1

The water of Isidis Bay was the color of a bruise or a clematis petal, sparkling with sunlight that glanced off waves just on the verge of whitecapping. The swell was from the north, and the cabin cruiser pitched and yawed as they motored northwest from DuMartheray Harbor. A bright day in spring, Ls 51, m-year 79, A.D. 2181.

Maya sat on the upper deck of the boat, drinking in the sea air and the flood of blue sunlight. It was a joy to be out on the water like this, away from all the haze and junk on shore. Wonderful the way the sea could not be tamed or changed in any way, wonderful how when one got out of the sight of land one rocked on blue wilderness again, always the same no matter what happened back there. She could have sailed on, all day every day, and each slide down the waves a little roller-coaster ride of the soul.

But that wasn’t what they were about. There ahead white-caps broke over a broad patch, and beside her the boat’s pilot brought the wheel over a spoke or two, and knocked the throttle down a few rpm. That white water was the top of Double Decker Butte, now a reef marked by a black buoy, clanging a deep bongBong, bongBong, bongBong.

Mooring buoys were scattered around this big nautical church bell. Their pilot steered to the nearest one. There were no other boats anchored here, or visible anywhere; it was as if they were alone in the world. Michel came up from below and stood by her, hand on her shoulder as the pilot cut the throttle, and a sailor in the bow below them reached out with a boat hook and snagged the buoy, clipped their mooring rope onto it. The pilot killed the engine and they drifted back on the swells till the mooring line tugged them short into one swell, with a loud slap and a fan of white spray. They were at anchor over Burroughs.

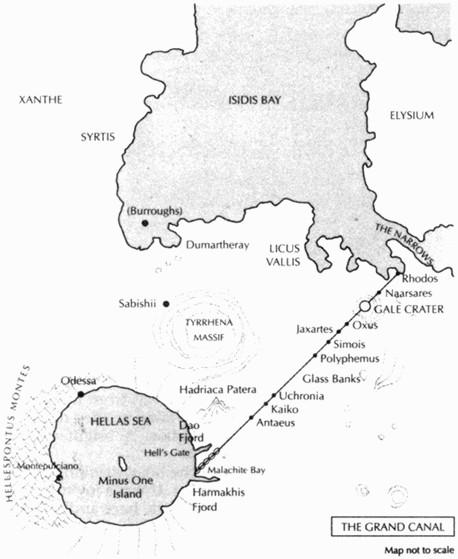

THE GRAND CANAL

• • •

Down in the cabin Maya got out of her clothes and pulled on a flexible orange dry suit: suit and hood, booties, tank and helmet, lastly gloves. She had only learned to dive for this descent, and every part of it was still new, except for the sensation of being underwater, which was like the weightlessness of space. So once she got over the side of the boat and into the water, it was a familiar feeling: sinking down, pulled by the weight belt, aware that the water around her was cold, but not feeling it in any real way. Breathing underwater; that was odd, but it worked. Down into the dark. She let go and swam down, away from the little pin of sunlight.

• • •

Down and down. Past the upper edge of Double Decker Butte, past its silvered or coppery windows, standing in rows like mineral extrusions or the one-way mirrors of observers from another dimension. Quickly gone in the murk, however, and she dream-parachuted down again, down and down. Michel and a couple others were following her, but it was so dark that she couldn’t see them. Then a robot trawl shaped like a thick bed frame sank past them all, its powerful headlights shooting forward long cones of crystalline fluidity, cones so long that they became one blurry diffuse cylinder, flowing this way and that as the trawl dipped and bobbed, striking now a distant mesa’s metallic windows, now the black muck down on the rooftops of the old Niederdorf. Somewhere down there, the Niederdorf Canal had run— there, a gleam of white teeth— the Bareiss columns, impervious white under their diamond coating, about half-buried in black sand and muck. She pulled up and kicked her fins back and forth a few times to stop descending, then pushed a button that shot some compressed air into one part of her weight belt, to stabilize herself. She floated then over the canal like a ghost. Yes; it was like Scrooge’s dream, the trawl a kind of robot Christmas Past, illuminating the drowned world of lost time, the city she had loved so much. Sudden darts of pain lanced through her ribs; mostly she was numb to any feeling. It was too strange, too hard to understand or believe that this was Burroughs, her Burroughs, now Atlantis at the bottom of a Martian sea.

Bothered by her lack of feeling, she kicked hard and swam down the canal park, over the salt columns and farther west. There on the left loomed Hunt Mesa, where she and Michel had lived in hiding over a dance studio; then the broad black upslope of Great Escarpment Boulevard. Ahead lay Princess Park, where in the second revolution she had stood on a stage and given a speech to a huge throng; the crowd had stood just below where she was floating now. Over there— that was where she and Nirgal had spoken. Now the black bottom of a bay. All of that, so long ago— her life— They had cut open the tent and walked away from the city, they had flooded it and never looked back. Yes, no doubt Michel was right, this dive was a perfect image of the murky processes of memory; and maybe it would help to see it; and yet . . . Maya felt her numbness, and doubted it. The city was drowned, sure. But it was still here. Anytime they wanted to someone could rebuild the dike and pump out this arm of the bay, and there the city would be again, drenched and steaming in the sunlight, safely enclosed in a polder as if it were some town in the Netherlands; wash down the muddy streets, plant streetgrass and trees, clean out the mesa interiors, and the houses and the shops down in the Niederdorf, and up the broad boulevards— polish the windows— and there you would have it all again— Burroughs, Mars, on the surface and gleaming. It could be done; it even made sense, almost, given how much excavation there had been in the nine mesas, given that Isidis Bay had no other good harbor. Well, no one would ever do it. But it could be done. And so it was not really like the past at all.

Numb, and feeling more and more chill, Maya shot more air into the weight belt, turned and swam back up the length of Canal Park, back toward the light trawl. Again she spotted the row of salt columns, and something about them drew her. She kicked down to them, then swam just over the black sand, disturbing the rippled surface with the downdraft from her fins. The rows of Bareiss columns had bracketed the old canal. They looked more tumbledown than ever now that their symmetricality was ruined by half burial. She remembered taking afternoon walks in the park, west into the sun, then back, with the light pouring past them. It had been a beautiful place. Down among the great mesas it had been like being in a giant city of many cathedrals.

There beyond the columns was a row of buildings. The buildings were the anchoring point for a line of kelp; long trunks rose from their roofs into the murk, their broad leaves undulating gently in a slow current. There had been a café in the front of that end building, a sidewalk café, partly shaded by a trellis covered with wisteria. The last salt column served as a marker, and Maya was sure of her identification.

She swam laboriously into a standing position, and a time came back to her. Frank had shouted at her and run off, no rhyme or reason as usual with him. She had dressed and followed him, and found him here hunched over a coffee. Yes. She had confronted him and they had argued right there, she had berated him for not hurrying up to Sheffield . . . she had knocked a coffee cup off the table, and the handle had broken off and spun on the ground. Frank got up and they walked away arguing, and went back to Sheffield. But no, no. That wasn’t how it had been. They had quarreled, yes, but then made up. Frank had reached across the table and held her hand, and a great black weight had lifted off her heart, giving her a brief moment of grace, of being in love and being loved.

One or the other. But which had it been?

She couldn’t remember. Couldn’t be sure. So many fights with Frank, so many reconciliations; both could have happened. It was impossible to keep track, to remember what had happened when. It was all blurring together in her mind, into vague impressions, disconnected moments. The past, disappearing entirely. Small noises, like an animal in pain— ah— that was her throat. Mewling, sobbing. Numb and yet sobbing, it was absurd. Whatever had happened then, she just wanted it back. “Fuh.” She couldn’t say his name. It hurt, as if someone had stuck a pin in her heart. Ah— that was feeling, it was! It couldn’t be denied; she was gasping with it, it hurt so. One couldn’t deny it.

She pumped the fins slowly, floated off the sand, up away from the rooftops anchoring their kelp. Sitting miserably at that café table, what would they have thought if they had known that a hundred and twenty years later she would be swimming overhead, and Frank dead all that time?

End of a dream. Disorientation, of a shift from one reality to another. Floating in the dark water brought back some of the numbness. Ah but there it was, that pinprick pain, there inside, encysted— insisted— hold on to it forever, hold on to any feeling you can, any feeling you can dredge up out of all that muck, anything! Anything but the numbness; sobbing in pain was rapture compared to that.

And so Michel was proved right again, the old alchemist. She looked around for him; he had swum off on voyages of his own. Quite some time had passed, the others were making their rendezvous in the cone of light before the trawl, like tropical fish in a dark cold tank, drawn to the light in hopes of warmth. Dreamy slow weightlessness. She thought of John, floating naked against black space and crystal stars. Ah— too much to feel. One could only stand a single shard of the past at a time; this drowned city; but she had made love to John here too, in a dorm somewhere in the first years— to John, to Frank, to that engineer whose name she could seldom recall, no doubt to others besides, all forgotten, or almost; she would have to work on that. Encyst them all, precious stabs of feeling held in her forever, till death did they part. Up, up, up, among the colorful tropical fish with their arms and their legs, back into the light of day, blue sunlight, ah God yes, ears popping, a giddiness perhaps of nitrogen narcosis, rapture of the deep. Or the rapture of human depth, the way they lived and lived, giants plunged through the years, yes, and what they held on to. Michel was swimming up from below, following her; she kicked then waited, waited, clasped him and squeezed hard, ah, how she loved the other’s solidity in her arms, that proof of reality, she squeezed thinking thank you Michel you sorcerer of my soul, thank you Mars for what endures in us, drowned or encysted though it may be. Up into the glorious sun, into the wind, strip off the suit with cold clumsy fingers, pull it off and step out of it chrysalislike, careless of the power of the female nude over the male eye, then suddenly aware of it, give them that startling vision of flesh in the sunlight, sex in the afternoon, breathe deep in the wind, goose-pimpling all over with the shock of being alive. “I’m still Maya,” she insisted to Michel, teeth chattering; she hugged her breasts and toweled off, luxury of terry cloth on wet skin. She pulled on clothes, whooped at the chill of the wind. Michel’s face was the image of happiness, the deification, that mask of joy, old Dionysius, laughing aloud at the success of his plan, at the rapture of his friend and companion. “What did you see?” “The café— the park— the canal— and you?” “Hunt Mesa— the dance studio— Thoth Boulevard— Table Mountain.” In the cabin he had a bucket of champagne on ice, and he popped the cork and it shot off into the wind and landed lightly on the water, then floated off on the blue waves.

• • •

But she refused to say any more about it. She would not tell the story of her dive. The others did and then it was her turn, somehow, and the people on the boat were looking at her like vultures, eager to gulp down her experiences. She drank her champagne and sat silently on the upper deck, watching the broad-sloped waves. Waves looked odd on Mars, big and sloppy, impressive. She gave Michel a look to let him know she was all right, that he had done well to send her under. Beyond that, silence. Let them have their own experiences to feed on, the vultures.

The boat returned to DuMartheray Harbor, which consisted of a little crescent of marina-platted water, curving under part of the apron of DuMartheray Crater. The slope of the apron was covered with buildings and greenery, right up to the rim.

They disembarked and walked up through the town, had dinner in a rim restaurant, watching sunset flare over the water of Isidis Bay. The evening wind fell down the escarpment and whistled offshore, holding the waves up and tearing spray off their tops, in white plumes crossed by brief rainbow arcs. Maya sat next to Michel, and kept a hand on his thigh or shoulder. “Amazing,” someone said, “to see the row of salt columns still gleaming down there.”

“And the rows of windows in the mesas! Did you see that broken one? I wanted to go in and look, but I was afraid.”

Maya grimaced, concentrated on the moment. People across the table were talking to Michel about a new institute concerning the First Hundred and other early colonists— some kind of museum, a repository of oral histories, committees to protect the earliest buildings from destruction, etc., also a program to provide help for superelderly early settlers. Naturally these earnest young men (and young men could be so earnest) were particularly interested in Michel’s help, and in finding and somehow enlisting all of the First Hundred left alive; twenty-three now, they said. Michel was of course perfectly courteous, and indeed seemed truly interested in the project.

Maya couldn’t have hated the idea more. A dive into the wreckage of the past, as a kind of smelling salts, repellent but invigorating— fine. That was acceptable, even healthy. But to fix on the past, to focus on it; disgusting. She would have happily tossed the earnest young men over the rail. Meanwhile Michel was agreeing to interview all the remaining First Hundred, to help the project get started. Maya stood up and went to the rail, leaned against it. Below on the darkening water luminous plumes of spray were still blowing off the top of every wave.

• • •

A young woman came up beside her and leaned on the railing. “My name is Vendana,” she said to Maya, while looking down at the waves. “I’m the Green party’s local political agent for the year.” She had a beautiful profile, clean and sharp in a classic Indian look: olive-skinned, black-eyebrowed, long nose, small mouth. Intelligent subtle brown eyes. It was odd how much one could tell by faces alone; Maya was beginning to feel she knew everything essential about a person at first glance. Which was a useful ability, given that so much of what the young natives said these days baffled her. She needed that first insight.

Greenness, however, she understood, or thought she did; actually an archaic political term, she would have thought, given that Mars was fully green now, and blue as well. “What do you want?”

Vendana said, “Jackie Boone, and the Free Mars slate of candidates for offices from this area, are traveling around campaigning for the upcoming elections. If Jackie stays party chair again, and gets back on the executive council, then she’ll continue working on the Free Mars plan to ban all new immigration from Earth. It’s her idea, and she’s been pushing it hard. Her contention is that Terran immigration can all be redirected elsewhere in the solar system. That isn’t true, but it’s a stance that goes over very well in certain quarters. The Terrans, of course, don’t like it. If Free Mars wins big on an isolationist program, we think Earth will react very badly. They’ve already got problems they can barely handle, they need to have what little out we provide. And they’ll call it a breaking of the treaty you negotiated. They might even go to war over it.”

Maya nodded; for years she had felt a heightening tension between Earth and Mars, no matter Michel’s assurances. She had known this was coming, she had seen it.

“Jackie has a lot of groups lined up behind her, and Free Mars has had a supermajority in the global government for years now. They’ve been packing the environmental courts all the while. The courts will back her in any immigration ban she cares to propose. We want to maintain the policies as set by the treaty you negotiated, or even widen immigration quotas a bit, to give Earth as much help as we can. But Jackie’s going to be hard to stop. To tell you the truth, I don’t think we know quite how. So I thought I’d ask you.”

Maya was surprised: “How to stop her?”

“Yes. Or more generally, to ask you to help us. I think it will take unpisting her personally. I thought you might be interested.”

And she turned her head to look at Maya with a knowing smile.

There was something vaguely familiar in the ironic smile lifting that classic little full-lipped mouth, something which though offensive was much preferable to the wide-eyed enthusiasm of the young historians pestering Michel. And as Maya considered it, the invitation began to look better and better; it was contemporary politics, an engagement with the present. The triviality of the current scene usually put her off, but now she supposed that the politics of the moment always looked petty and stupid; only later did it take on the look of respectable statecraft, of immutable History. And this issue could prove to be important, as the young woman had said. And it would put her back in the midst of things. And of course (she did not think this consciously) anything that balked Jackie would have its own satisfactions. “Tell me more about it,” Maya said, moving down the balcony out of earshot of the others. And the tall ironic young woman followed her.